Estuary English

It seems as if class and regional differences are very much to the fore at the moment. No surprise there I suppose, nor the increased discussion of accent as a status marker. When I was growing up my mother was at pains to correct her children’s accents so that we didn’t pick up ‘lazy’ habits, such as glottal stops instead of T at the end of a word like ‘hat’, or saying (shudder!) ‘tomorrer’ or ‘sumfingk’. By lazy of course she meant working class, particularly Cockney, and it was all tied up with her aspirations for us. Her reasoning was that Cockney-sounding females didn’t become (or marry!) doctors or teachers. Similarly, she didn’t want me to learn shorthand typing (as she had) because she felt I’d then be ‘stuck’ in secretarial jobs. But whether I learned to type or not (I didn’t), her main concern was that I should be ‘well-spoken’, because such an accent would mark me as middle class, with all the social and economic advantages she believed that would bring.

It’s funny how things change. These days communications advisers tell people in the public eye to tone down a public-school accent in order to sound ‘friendlier’ or ‘one of the people’. It’s not just accent of course – it’s also the avoidance of Latin sayings or words like ‘hence’ or ‘thus’.) Hence (oops!) the rise and rise of ‘Estuary English’. Actually it’s generally known to linguists as ‘Southeastern Regional Standard’ or ‘London Regional Standard’, since ‘Estuary English’ has been used too often as a mild slur.

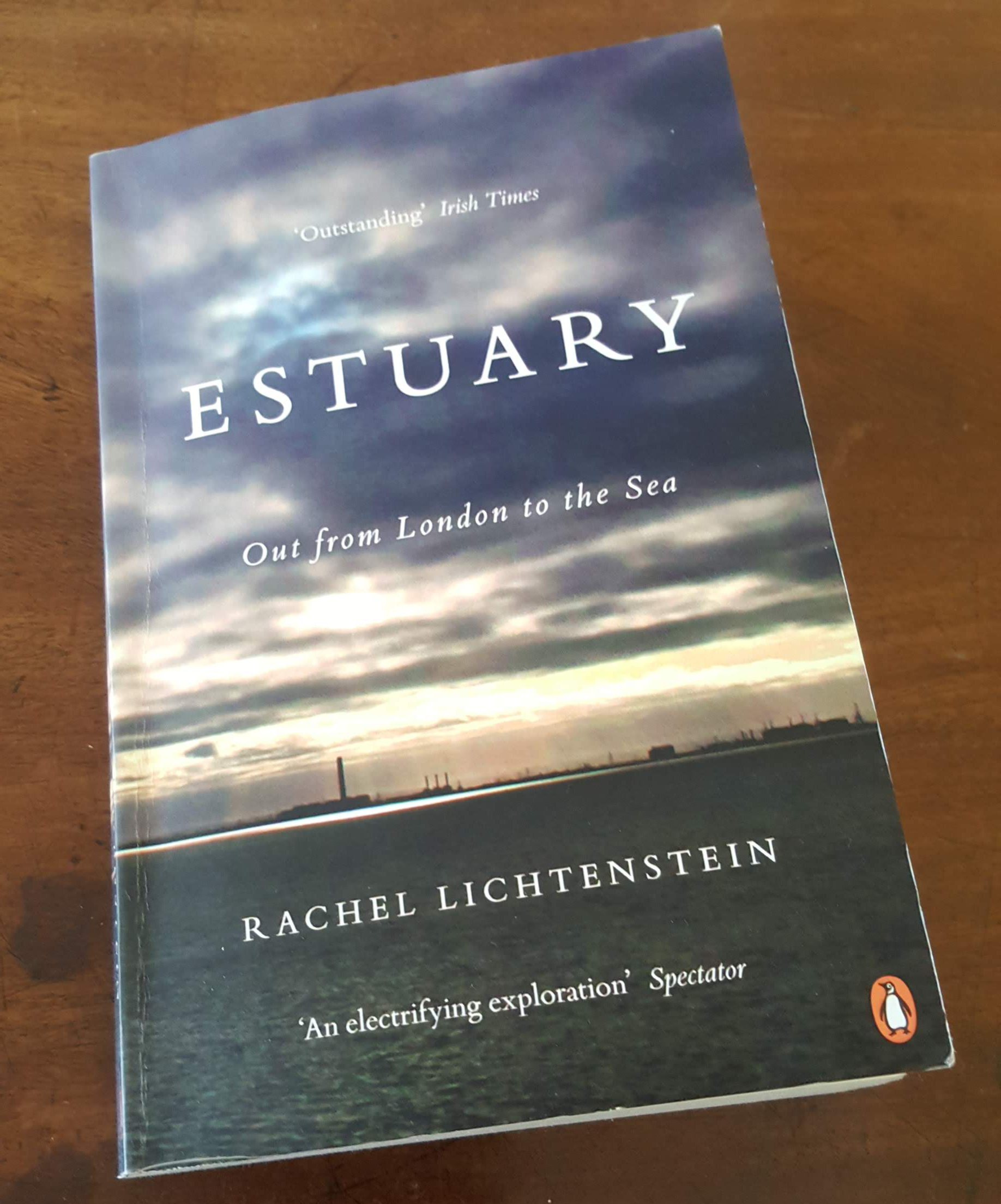

This preamble is by way of introducing a wonderful book by Rachel Lichtenstein, Estuary (Penguin 2017). When I picked this up I realised right away how little I knew about the Thames Estuary, its history, communities, traffic and commerce, even its geography. Considering I grew up not so far from the Thames at Greenwich, I’m ashamed to say I couldn’t have pinpointed on a map any of the place names downriver, even the historic ones – Tilbury, Gravesend, Canvey Island. I didn’t even realise Southend was in the estuary at all, imagining it to be much further around the Essex coast. Now I’m as much of an Estuary girl as I am a Londoner, certainly by my accent (which in its unselfconscious state is a bit rough around the edges whilst still being ‘well spoken’ enough to satisfy my mum. Sometimes it slips though…) And I find the mysteries of the sea compelling, particularly when it’s as well-written as this. (I remember devouring Adam Nicolson’s Sea Room some years ago… highly recommended.)

Lichtenstein takes us on a number of journeys, both on the water and into the region’s many communities. We learn how difficult it is to navigate the treacherous shifting sandbanks, how the area has changed and is changing still with the decline of old industries like cockling and the building of the gargantuan London Gateway container port. There are ‘more shipwrecks per square foot than anywhere else along the UK coastline […] over six hundred known wrecks in the main shipping channel alone’, and the remains of plenty more, from as far back as the Bronze Age.

The book is entrancing with its vocabulary of boats, fishing and coastal communities. At times it read like a foreign language to a landlubber like me who doesn’t know a mizzen from a Genoa (although there is a glossary to help.) But it doesn’t detract from the drama, quite the opposite. And in places it feels like poetry.

We turned the engine off for a while and circled the fort in silence, listening to the gentle sound of the boat cutting through the water, the creaking of the shrouds, the ensign flapping at the stern, the rattle of the boom and the occasional lonely call of a seagull, and then, in the distance, the great boom of guns being tested on Foulness Island.[…] A coastguard border-control ship came towards us, moving quickly through the water. Seawater splashed up over the bow; the wash made us lurch violently from side to side. There was another big explosion over at Foulness: a great cloud of black smoke rose over the Essex coastline. (Estuary, Chapter 26, ‘Barrow Deep’)

The above photo is from a fascinating blog about mid to late-twentieth century life in London, A London Inheritance.

I wrote my first ever poem in one of Rachel’s classes as part of my MA. She was then writing about Hatton Gardens and took us on an interesting tour of Farringdon. I didn’t know about this book, so thank you for highlighting it. I come from Coventry and in the CCFC song they sing, ‘we speak with an accent exceedingly rare, you want a Cathedral we’ve got one to spare, in our Coventry homes,’ I never knew I had an accent until I left the city.

Hi Peter – how interesting, your connection with Rachel! My husband is from Coventry, but hasn’t got the local accent, for various reasons. I would say he sounds completely different from his brother, but neither is that aware of it. Everyone has an accent of course; it would be impossible to speak without one. It’s quite hard to categorise one’s own though.

Excellent recommendation Robin – I’ve got someone in mind who will love this for their birthday, and having recently trained it from Stratford to Broadstairs via Chatham it feels quite resonant. Flat ground big skies.